When you talk, you hear from the other side

Vinyl and Set of Eight Glass Collages

Audio by Bhob Rainey (with contributions from Jason Lescalleet)

Art by Nancy Bernardo

Limited edition of three sets, $500 each

Buy or

Request a digital or personal showing (Philadelphia area)

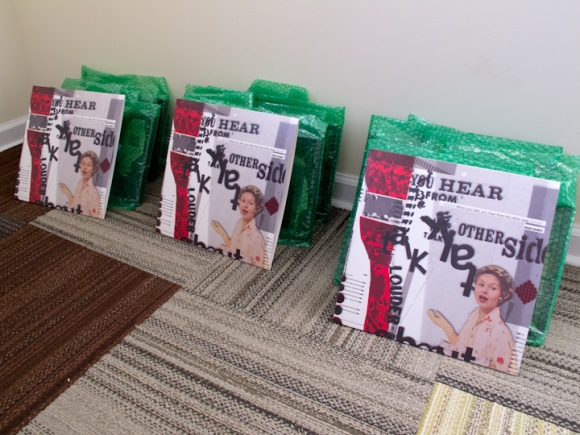

Image Galleries: Set 1 Set 2 Set 3

There is a lot to say about this release, and I do my best to say it in detail below. But, to summarize at the top, what we have here is a limited edition of three (currently two remaining) sets of eight layered glass collages by Nancy Bernardo and one LP (or perhaps something between an EP and an LP) by me. That is, each set includes eight collages and one vinyl record.

The vinyl contains a piece of audio work that was constructed from a found wire spool (the recording medium that preceded magnetic tape). The material on the spool comes from 1951 and 1952 and consists of a wide array of amateur attempts at humor, imitation, interviews, song, and advertisement. A more detailed description is below.

The vinyl contains a piece of audio work that was constructed from a found wire spool (the recording medium that preceded magnetic tape). The material on the spool comes from 1951 and 1952 and consists of a wide array of amateur attempts at humor, imitation, interviews, song, and advertisement. A more detailed description is below.

The wire spool material eventually melts into a hypnotic electronic piece (again, more below regarding this and dreams and death), part of which was done in collaboration with Jason Lescalleet.

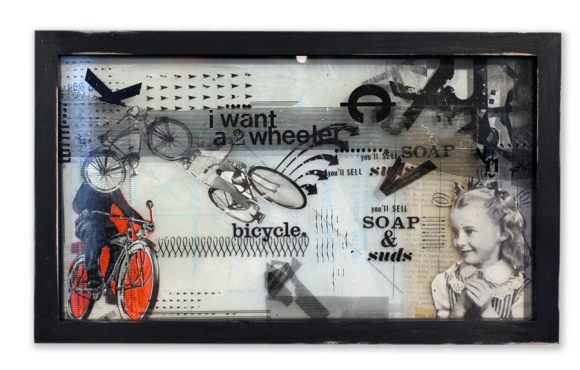

Nancy Bernardo, whose work frequently involves iconic imagery from the ’50s, created her collages in response to this piece, forming something of a timeline to the audio. The layers in this work are quite striking and somewhat difficult to represent in an image. Below is an attempt to show the play of transparency in one of the pieces.

To be as clear as possible, when you buy one of these editions, you get eight, unique collages and one vinyl record.

To be as clear as possible, when you buy one of these editions, you get eight, unique collages and one vinyl record.

We understand that visual art can seem expensive to the average music-buyer, and we are keeping the price of this as low as possible (a single collage from this set could easily cost $500). We also have more detailed images and can arrange viewings in the Philadelphia area upon request.

We understand that visual art can seem expensive to the average music-buyer, and we are keeping the price of this as low as possible (a single collage from this set could easily cost $500). We also have more detailed images and can arrange viewings in the Philadelphia area upon request.

There is also an edition of 250 vinyl-only copies for $7.50. Order

And now for a more detailed account:

When you talk, you hear from the other side was constructed from two wire spool recordings found in an antique shop in Western Massachusetts. The content of the spools makes it clear that they were recorded in 1951 and 1952 on a machine that was a Christmas gift to a nine-year-old boy.

Unsurprisingly, most of the first (and longest) spool is populated by Christmas revelry and multi-generational goofing, but there are captivating passages from both before and after Christmas day: a salesman demoing the unit to various customers; an interview between a snotty eleven-year-old boy and a spirited, if bewildered, four-year-old girl; etc.

When I first heard these recordings, I was with a small group of people, and we listened and laughed for a few hours before I suggested that maybe we should archive the material. We’d already seen the wire snap a few times during playback. (This was a general problem with recording on wire; one that was frequently remedied via a faux- soldering job with the smoldering end of a cigarette. We just tied the wire back together.)

The machine had a line-level output, but the connection hardly resembled any modern standard. So, an RCA cable was stripped of its plugs on one side, and the bare cables were stuck into the output. This worked surprisingly well, and the recording was successfully archived.

Recordings like this can really nag at you. I wanted to be happy just having an amusing trace of a mid-century, middle class, American Christmas and to be reminded of the ridiculous things a recording device draws from people when they feel their way around its place in their lives. But then there’s the voice that says, “Do something with this.”

To be fair, this voice is pretty easy to activate and not always the best judge of material that should have something “done” to it. Still, there was something special about this recording: kids and adults messing around in equal quantities; a newscast (captured from a brand new television) describing the Alger Hiss / Whittaker Chambers trial; a girl explaining that she loves her dog because “she likes to tear clothes”; a man offering to sing “Home on the Range” in “Jewish” (and forgetting most of the words); countless incidents of “regular” people adopting a media affect and stumbling all over themselves. I eventually started doing stuff to the material.

There are a lot of pieces of music, particularly in the realm of Musique Concrète, that exploit and manipulate spoken words to elicit what has become a fairly typical haunting / lecturing effect. I’ll admit that this is the angle I first took with this material: layers of “alien” sounds interspersed with voices from ANOTHER TIME(!) that simultaneously anchor (via comprehensible speech) and destabilize (via disembodiment and decontextualization) the musical experience.

This strategy didn’t work out for me. Perhaps in the hands of someone like Lionel Marchetti, it would have had a brilliant outcome. To me, it sounded forced. Worse, it obscured the qualities of speech and idiosyncratic language that attracted me to the material in the first place. I decided that, instead of using pieces of this recording for some other musical purpose, I would try to amplify its inherent resonances and expose whatever was already musical within it.

With that in mind, the construction of When you talk, you hear from the other side became more effortless. I restricted myself to few effects (the majority of manipulations involve playing the recording back through different speakers) and few musical gestures (sometimes loops of wire and / or microphone noise are added to highlight shifts in content and timbre). The bulk of the piece relies on layering and editing.

By avoiding grand gestures and virtuosic electronic manipulations, I discovered that I was basically showing a love for these people and the glimpse of the world that their recording gave me. The piece became a fond, dynamic remembering of a life I never lived with people I never met. So, at the end, in the spirit of nostalgic indulgence, I let it all fall asleep and dream about itself. Eventually, the dream itself fell asleep; a sleep without dreams (Side B: The other side of what).

Of course, when I’m talking about the piece dreaming, I’m talking about the more overtly “musical” parts (and, really, I would say “dying” instead of “dreaming”, if that didn’t make people feel bad). I say dreaming (or dying) because the music keeps erasing itself; peeling away; evaporating; no longer concerned that you’re listening. The other side of talking.

And this music sat with me for some time. I would revisit it now and then, make some tweaks, but never push to release it. “To publish anything is folly and evidence of a certain defect of character.” (at least, that’s what Thomas Bernhard says on page 34 of the 1984 University of Chicago edition of Concrete). While I’m not without this character defect, I couldn’t make the connection between this music and an “anonymous” audience. I couldn’t imagine it in the world by itself.

Nancy Bernardo presented the opportunity to give it some company. She was asked to participate in a “duos” exhibit, pairing visual and sonic artists, and proposed that I provide the sonic element. Normally, I would take this as an opportunity to do something new, but Nancy’s work has so much in common with When you talk, you hear from the other side, from its material to its production, that I sent her a copy to see if it resonated with her.

It did, and the result was a set of eight layered glass collages that visualize what Nancy felt were key moments in the piece. I loved the set. I felt that it gave me permission to let this music loose and stop protecting it (i.e., protecting myself from being embarrassed by it). Nancy agreed to make two more sets, and I went ahead and pressed a record.